Sometimes, when the sex is really good, the colors come.

As Holly approaches orgasm, a pastel filter descends over her vision, lasting through her climax and into the afterglow. She tends to see just one or two hues in the form of blurry orbs: seafoam green, bright yellow, black and red, hot pink or white. It’s like peering through tinted glasses, she says, or looking up at an aurora-splashed sky. (Because of the intimate nature of the subject matter, some of the sources interviewed for this story asked to be identified only by their given name or to remain anonymous.)

“It’s been happening as long as I’ve been having sex, as far as I know,” says Holly, a 26-year-old from California—though it doesn’t happen every time. “It’s gotten more intense and colorful as my connections have been better and my orgasms have been better.” When, at 20 years old, she first talked about her experiences with her friends, they were bemused. “I didn’t feel surprised,” she says. “It was just kind of affirming that it was special.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In people with synesthesia, the brain’s sensory wiring can get crossed. Orgasm synesthesia, or sexual synesthesia, is a little-known form of the phenomenon. Roughly 4 percent of people experience some kind of synesthesia; a common form is the association of colors with certain letters, numbers or sounds. In people with sexual synesthesia, it’s the sensation of orgasm (or occasionally even sensual touch) that provokes the wash of color.

This experience might be more common than we realize: to seek personal accounts, I reached out to friends and my wider communities in New Zealand, asking to hear from anyone who sees colors when they orgasm—and around a dozen immediately responded with their stories.

Some people describe their colors as “like stained glass in a cathedral,” while for others, they’re more like “artisanal soaps” or “paint being hurled at a canvas.” Francesca Radford, a 33-year-old who lives in Auckland, says she tends to see patterns, usually zebra print or reptile scales. Rob, a Web developer in Wellington, says he has had orgasms that begin with pinprick of light and grow into a chaotic mandala, accompanied by vibrations and a roaring in his ears. Cherry Chambers, a bookkeeper from Auckland, once felt she was “shot up out of the deep ocean into a night sky—basically a whirl of colors rushing past,” she says. “That was one of the most intense orgasms I have ever had.”

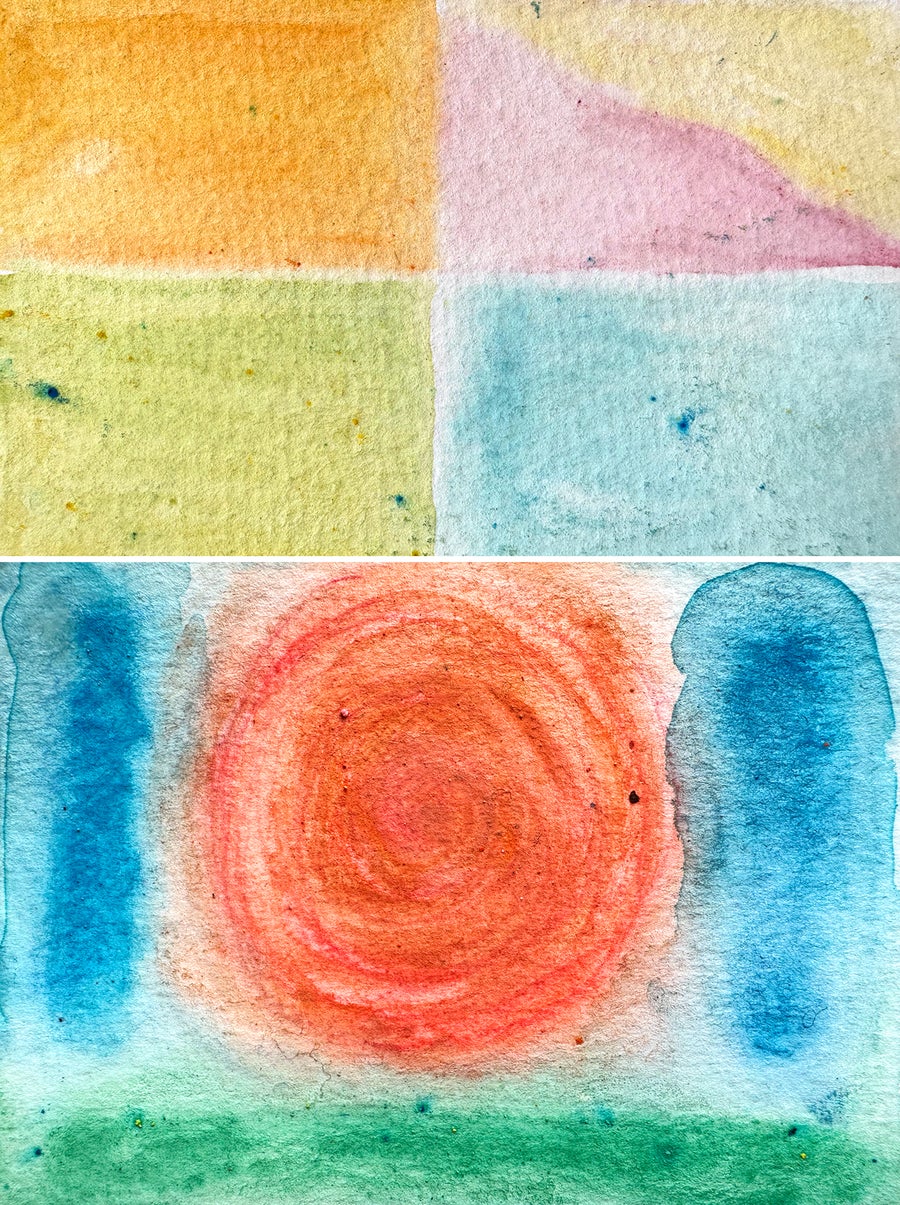

Cherry Chambers, who has sexual synesthesia, painted one of her orgasms in an effort to convey the experience to her boyfriend.

This curious phenomenon has been sporadically documented for decades—the first academic mention is in a 1973 book by psychologist Seymour Fisher called The Female Orgasm—but it has received very little scientific attention, says Richard Cytowic, a pioneering synesthesia expert and a professor of neurology at George Washington University.

In the 1980s Cytowic had to convince colleagues that synesthesia itself was worthy of scientific investigation. This type of sensory crossover is now widely accepted and studied, but its sexual variety is less so. “It’s the kind of thing that’s going to raise eyebrows in university departments,” Cytowic says. “Even though sex is wildly popular, science about it is not.”

Now, though, neuropsychology researcher Cathy Lebeau is trying to learn more. Lebeau, whose own form of synesthesia makes her perceive letters as colored, became fascinated by accounts that suggested that sexual synesthesia could alter consciousness. For her doctoral research at the University of Quebec, she and her supervisor, neuropsychologist François Richer, interviewed 16 people with sexual synesthesia (who all also had other forms of synesthesia) and 11 people with no synesthesia, and had them complete a series of standardized questionnaires.

All but one of the participants were women, but that doesn’t mean the phenomenon is necessarily linked to the female brain. Scientists used to think all forms of synesthesia were more common in women, Lebeau points out, but subsequent studies have shown that’s likely because of selection bias. “Women like to talk about their experiences, and they’re more comfortable doing it,” she says.

Holly, who has sexual synesthesia, painted five different ways that she has experienced the phenomenon (four at top and one at bottom).

While conducting the study—which was released as a preprint paper and has been not yet been peer-reviewed—Lebeau was surprised by how similar the participants’ reported experiences were, regardless of age or whether they were from Quebec, the U.S. or Europe. “People who didn’t know each other … were telling me almost the same thing,” she says.

For instance, almost all of them reported that they needed to feel comfortable and confident with a sexual partner to see the colors and that the phenomenon rarely happened during masturbation or casual encounters. Many interviewees said they had to be in a relaxed, passive state—and often in the missionary position. And though the specifics of their visions differed, many mentioned dissociative experiences, particularly “the feeling that they’re expanding over the room and that they’re not there anymore—that they’re tripping, really,” Lebeau says.

In fact, some people with sexual synesthesia say they are momentarily transported to bizarre, one-off scenes at the moment of orgasm. Once, an intricate architectural image of a staircase and lamp grew out of a beige mist before Ruby Watson’s eyes. On another memorable occasion, she says, she briefly felt like she had become a panda chilling alongside another panda. She’s mystified by where these images come from. “We weren’t sexy pandas,” she says. “We were just chewing bamboo, getting on with life.”

Such scenes can completely overwhelm Watson’s spatial awareness and vision, and they don’t necessarily enhance her connection with her husband. “I’m not staring into my lover’s eyes,” she explains. “I’m seeing a baroque light fitting.” A previous study found that although people with sexual synesthesia reported better sexual function overall than people without synesthesia, there was some evidence that they had slightly less sexual satisfaction because of feelings of isolation caused by their unusual sensory experiences.

Others insist synesthesia improves their sexual experience. Michelle Duff sees colors and occasionally scenes—a coven of witches on broomsticks, a sea alive with jellyfish—but because she feels like she’s one of the witches or jellies, perhaps “see” isn’t the right word. “It feels more immersive, like what I’m seeing is a visual embodiment of what I’m feeling. It’s all-consuming, but it doesn’t feel like I’ve gone off somewhere [without my partner],” she says. “It feels like we’re living out the scene together.”

For some, it can be awkward explaining these rainbow journeyings to their sexual partners. For others, that’s part of the fun. “My partners love it,” Holly says. “That’s such a thing, somebody popping their head up and being like, ‘What color?’ It’s one of the perks of being my lover.” Rob, the Web developer, says he once had the rare joy of making love to someone else with the condition. “That was a very fun time where we would compare notes afterwards,” he says. “It was so euphoric and shared and beautiful.”

Almost everyone Lebeau interviewed felt positively about their synesthesia, telling her it made their sexual experiences richer. One person told her that the absence of these sexual “fireworks” would turn her off a potential partner, even if he was otherwise perfect. “If I don’t have synesthesia when we sleep together, it’s a no,” she says. Clashing or ugly colors can also be turnoffs.

Another person I spoke with says she used to feel disturbed by the colors, textures, music and patterns she saw only during sex, and she worried that they were harbingers of schizophrenic hallucinations that run in her family. When she stumbled upon an article that explained how such symptoms can represent a type of synesthesia, she says she felt a “huge relief and freedom.”

There’s no established connection between sexual synesthesia and mental health conditions, though synesthesia in general has been linked to higher rates of anxiety in children and is a significant risk factor for developing post-traumatic stress disorder.

None of the 16 people with synesthesia in Lebeau’s study had psychiatric or neurological conditions. But 13 of them did report surprisingly intense consciousness alterations in daily life—a tendency that has also been observed in some studies of people with synesthesia in general. Some reported symptoms of a type of delusion called Capgras syndrome, in which a person momentarily thinks that a friend or family member has been replaced with an imposter, or Alice in Wonderland syndrome—which involves distortions of reality, including the impression that one’s body is shrinking or growing.

Lebeau hopes people with sexual synesthesia might help researchers learn more about the underlying mechanisms of consciousness by providing a kind of “healthy model” of severe consciousness alterations. Qualifying the differences in the brain between these benign perceptual disturbances and harmful hallucinations might help scientists better understand psychosis.

For now, scientists don’t know what’s happening in the brain during sexual synesthesia experiences. “It is hard to speculate on the anatomical or chemical basis of this type of synesthesia from the case descriptions alone,” says psychologist Jamie Ward of the University of Sussex in England. “It is an important first step,” he says of Lebeau and Richer’s research, though “in this particular study, it is hard to know which findings are specifically attributable to this phenomenon and which are due to synesthesia more generally. It would have been good to compare two groups of synesthetes directly—with and without these experiences.”

Lebeau would love to capture the brain activity of a person with sexual synesthesia at the multicolored moment of orgasm. Getting people to have connected, relaxed sex inside of a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine, however, presents certain practical and financial constraints. “Still, I think it’s doable,” she says. “If I had the money, in a perfect world…, that would be my dream.”

Further studies into this intriguing phenomenon would be worthwhile, Cytowic says. “Nature reveals herself through her exceptions,” he says, “and I think synesthetic orgasms might give us an additional clue into how synesthesia operates that we didn’t have before.”

[source_link