Vaccines are a marvel of modern medicine: the carefully tested and regulated technologies teach people’s immune systems how to fight off potentially fatal infections, saving both lives and health care costs.

But for as long as vaccines have existed, people have opposed them, and in recent years the antivaccine movement has gained visibility and power. Now the Department of Health and Human Services is led by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.—an environmental lawyer with no medical training and a history of antivaccine activism. And these lifesaving medical interventions are coming under threat.

Access to COVID vaccines this fall is already expected to be limited to people aged 65 years or older and to those with underlying health conditions that make them more vulnerable to severe disease. And in June Kennedy dismissed all 17 sitting members of a crucial vaccine oversight group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which, in the past, has made independent, science-based recommendations on vaccine access for people in the U.S. The dismissals came just weeks before the panel’s next scheduled meeting; Kennedy appointed eight new members in advance of the meeting, which is still set to begin on June 25.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

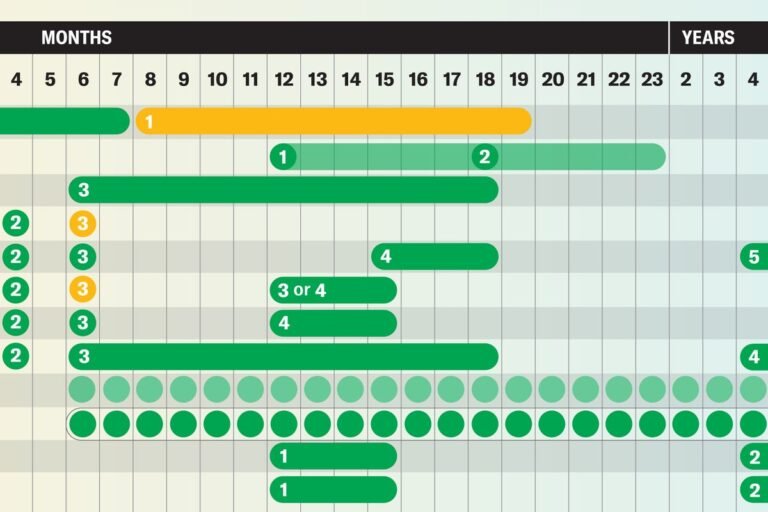

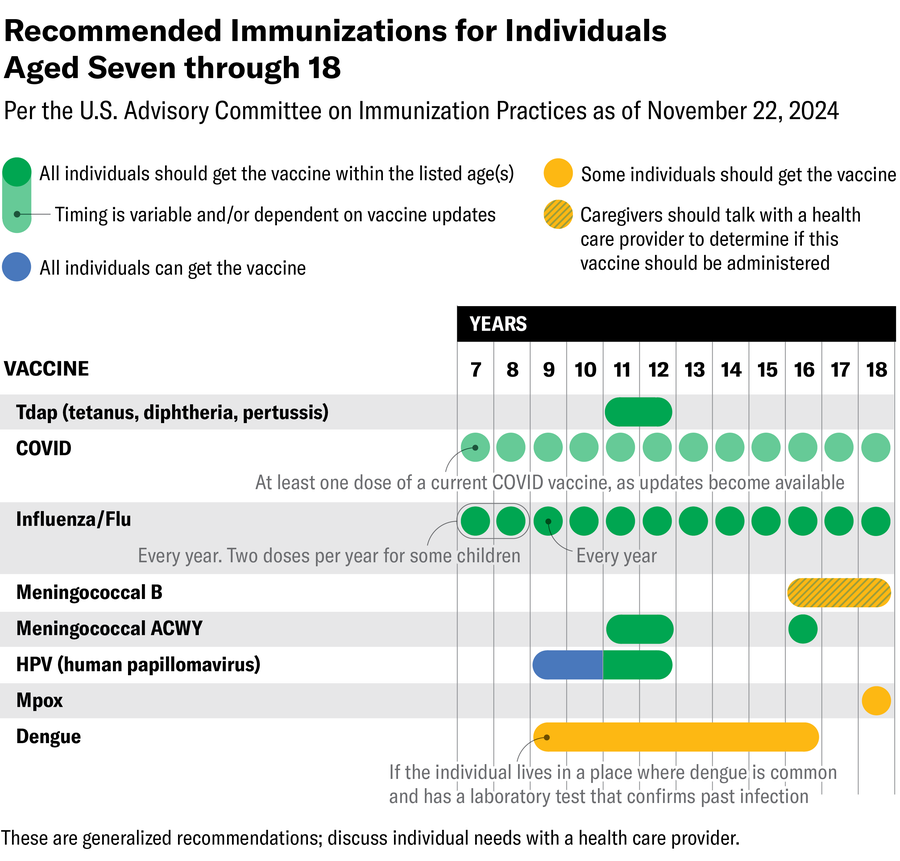

As a public resource, Scientific American has created graphics outlining the vaccines recommended by ACIP as of its final meeting in 2024.

Vaccine recommendations have always been in flux as new products have been developed and continuing research has suggested better practices: The COVID pandemic required brand-new vaccines for a novel virus, for example. And in the U.S., the stunning success of the HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccine led to its recommendation for everyone aged 26 or younger, meanwhile the oral polio vaccine was discontinued in favor of the inactivated injected vaccine.

But traditionally, these decisions have been made by scientists based on solid research done within the confines of accepted ethical practices. These principles mean, for example, that a vaccine’s side effects are carefully monitored and evaluated against its immune benefit and that potential replacement vaccines are tested against their predecessors, not—as Kennedy has proposed—an inert placebo that would leave people vulnerable to an infection that doctors already have the tools to combat.

Kennedy’s decision to replace ACIP wholesale and the comments he has made about deviating from standard vaccine policymaking practice suggest that new recommendations won’t be backed by established vaccine science—hence our reproduction of the vaccine recommendations as of the end of 2024.

Note that these are generalized recommendations; people should talk with their health care providers about individual risks and needs, as well as how to proceed after missing a dose. Pregnant people can consult additional resources from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for vaccines recommended during pregnancy. People planning to travel internationally should also check what vaccines are recommended for their destination and consult with a health care professional more than a month before departure.

Vaccines Recommended for Children

Jen Christiansen; Source: “Recommended Immunizations for Birth through 6 Years Old, United States, 2025.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Version dated to November 22, 2024. Accessed June 18, 2025 (primary reference)

Jen Christiansen; Source: “Recommended Immunizations for Children 7–18 Years Old, United States, 2025.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Version dated to November 22, 2024. Accessed June 18, 2025 (primary reference)

Vaccines Recommended for Adults

Jen Christiansen; Source: “Recommended Immunizations for Adults Aged 19 Years and Older, United States, 2025.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Version dated to November 22, 2024. Accessed June 18, 2025 (primary reference)

Infections These Vaccines Protect Against

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV): This respiratory virus hospitalizes an estimated 58,000 children and 177,000 older adults each year in the U.S. Annually in the country, it kills between 100 and 500 children under five years old and about 14,000 older adults.

Hepatitis A and B: Both of these viruses cause liver infections. Severe cases of hepatitis A can require liver transplants, while chronic cases of hepatitis B can lead to other liver problems, including liver cancer.

Rotavirus: This common gastrointestinal virus causes diarrhea that is sometimes severe enough to require hospitalization. Infections are most common in children under three years old, and the virus can withstand handwashing and common hand sanitizers.

Diphtheria: This bacterial infection has become rare in the U.S. through vaccination; before the vaccine was available, case rates could be as high as 200,000 annually. The infection can manifest in the respiratory system or the skin. Half of untreated people die; children under age five and adults more than 40 years old are most vulnerable.

Tetanus: Sometimes called lockjaw because an early symptom is muscle pain and spasms in the jaw, tetanus is caused by toxins from a bacterium. Doctors don’t have a cure for tetanus, and the infection has become rare in the U.S. only through vaccination.

Pertussis/whooping cough: This bacterial infection is sometimes nicknamed the “100-day cough” for its most characteristic symptom. U.S. infection levels have generally run between 10,000 and 20,000 diagnosed cases per year; the disease hospitalizes more than one in five infected children under six months old.

Haemophilus influenzae type b infection: This bacterium—unrelated to the influenza virus—causes a host of infections, including mild cases in the ears and lungs but also severe cases in systems such as the bloodstream and central nervous system. Before the vaccine was developed, the U.S. saw 20,000 severe infections annually in children under five years of age, and one in 20 of these cases was fatal.

Pneumococcal disease: The bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae can cause a range of infections, including so-called invasive infections that tend to be more serious. Pneumococcal disease can include pneumonia—pneumococcal pneumonia hospitalizes more than 150,000 people in the U.S. each year. But other types of pathogens also cause pneumonia, and pneumococcal disease can manifest anywhere in the body.

Polio: This virus most frequently causes asymptomatic infections, but symptomatic infections can have quite severe symptoms, including paralysis of one or more limbs or even of the muscles involved in breathing. Polio can also trigger new symptoms many years after the initial infection in what’s called postpolio syndrome.

COVID: In the five years since COVID emerged, this disease has contributed to the deaths of more than 1.2 million people in the U.S.; weekly death tolls remain in the hundreds. The virus also causes lingering and sometimes debilitating systemic issues known as long COVID, including in children.

Influenza: This respiratory virus is most prevalent in North America between October and May. Although many cases can be treated at home, flu infections can be very serious, particularly in young children and adults aged 65 or older, as well as people with immune issues and other chronic conditions. During the 2023–2024 season, the CDC reported 34 million cases of flu, 380,000 hospitalizations and 17,000 deaths.

Chickenpox: The varicella-zoster virus causes a characteristic itchy rash of small blisters that appear in conjunction with a fever, headache and other mild symptoms. Severe cases can cause more systemic infections, pneumonia, brain swelling and toxic shock syndrome. Adults who did not have chickenpox as a child are more vulnerable to serious infection.

Measles: Measles is one of the most contagious viruses known to experts, and historically most children contracted it before the age of 15. Doctors have no cure for measles; they can only treat its symptoms. About one in 1,000 cases causes brain inflammation; even rarer complications can occur years after the initial infection. The measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine has dramatically reduced caseloads in the U.S. since the late 1960s, however.

Mumps: Mumps is a viral infection characterized by the swelling of certain salivary glands, but other organs can also be affected, including the testicles, ovaries, brain, spinal cord and pancreas. Mumps can also trigger miscarriage early in pregnancy.

Rubella: Sometimes called German measles, rubella is a viral infection that is unrelated to measles but also causes a rash. For most people, rubella is a mild illness, but it triggers serious birth defects in as many as 90 percent of cases in which the virus infects someone during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Meningococcal disease: Infection of the blood or the membranes of the central nervous system by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis kills 10 to 15 percent of people who are treated; cases that aren’t fatal can include a range of long-term issues.

Human papilloma virus (HPV): Infection with this virus leaves people susceptible to cancer, particularly cervical cancer; nearly 38,000 cancers per year are attributed to the virus.

Mpox: The virus that causes mpox was first identified in 1958 but more regularly infects animals than humans. In 2022 it began spreading in people worldwide, however. The infection is characterized by a painful rash and flulike symptoms. The vaccine is only recommended for people who are likely to be exposed to the virus.

Dengue: Dengue is a mosquito-borne illness that is most common in tropical regions. In severe cases, it can damage blood vessels and interfere with the blood’s ability to clot. Vaccination is not available in the contiguous U.S., but it is available in U.S. territories and freely associated states for children aged nine to 16 who have had the disease before and live in a region where the infection is common.

Shingles: This infection is caused by the same virus as chickenpox, which remains in the body after a chickenpox infection. When the previously dormant virus reactivates, it can cause shingles, a painful localized rash that is most common in people aged 50 or older and can lead to ongoing pain, vision issues and neurological problems.

[source_link